This piece originally appeared in the GuildNotes, Issue 1, 2021

Community arts educators cannot authentically amplify youth voice and leadership without intentionally working to dismantle adultism in their programs, organizations, and collective action efforts. Adultism is the systematic mistreatment and disrespect of young people which in turn disregards their power and rights as full human-beings.

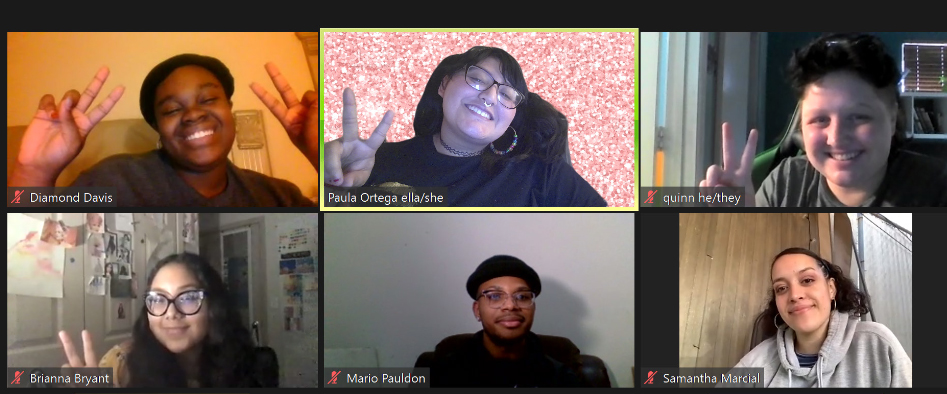

Too often, young people are shut out of or erased from policy and programming conversations and decision-making processes that directly affect their lives. Young people not only need a “seat at the table,” they need the holistic support of adult accomplices to create their own tables. In December 2020, young artists from the Creative Youth Development Partnership’s National Youth Network and Detroit’s CYD local network presented “Adultism,” a youth panel discussion on adultism and its impact on youth and adult spaces. The panel was organized by Paula Ortega, the Partnership’s National Youth Coordinator and core team member of Re:Frame Youth Arts Center (Phoenix), and Tanykia “Diamond” Davis, youth representative for the Detroit CYD Network and Living Arts (Detroit). They were joined in conversation by Mario Pauldon, poet and vocalist (Illinois); Sam Marcial, poet and dancer (California), Quinn Pursell, theatre artist (Arizona); and Brianna Bryant, engineer and applied artist (Michigan).

DIAMOND: What is your definition of adultism?

QUINN: My definition of adultism is just the assumption that the only people in the room with knowledge or experience, or just anything to offer, are the adults. Also, the assumption that the adults are the only authority figure in the room.

SAMANTHA: For me adultism is really about the power dynamics that exist between an adult and a young person and the abuse of that power dynamic.

DIAMOND: What have been your particular experiences with adultism?

BRIANNA: When we talk about older people I’m usually thinking about the grandmas and the grandpas—people that are significantly older than me. But all those figures in my life have passed away, so I really don’t have that many interactions with that group of older people. I feel like recently, though, as I start to come into adulthood, I’ve started to encounter adultism more at home, in terms of the dynamics between me and my mom. I live in a single parent household and that already has its own problems in and of itself. But as I’ve emerged into adulthood, I’ve started to form my own values, my own beliefs, my own dreams, and those tend to differ from my parents. I don’t know who else here is coming from a single parent home, but those parents tend to have their vision and idea of what they want their children to grow up to be. I’m glad my mother has a vision for me—has a passion to raise me to become something great—but I need to experience that greatness on my own and follow what I feel is great for me.

QUINN: My experience with adultism is generally really internal because [in] all of the youth-adult interactions that I’ve ever been a part of, or spaces that I’ve ever been in, the adults generally have all of the power. Whether that’s in a classroom or, for me, because I’m in theater, in a rehearsal room. As young people we tend to internalize that and think, “Oh, I don’t actually know what I’m talking about, I’m just going to defer to the older person because they of course know what they’re talking about,”when most of the time that’s not true. So, that’s been something that I think about a lot, especially while I am in a kind of limbo space between being a young person and an adult. How do I unlearn some of those experiences internally?

DIAMOND: How did you all start noticing and making it known that you were experiencing this?

SAMANTHA: I mostly experienced adultism before I got comfortable in my own voice. I wouldn’t say anything—I wouldn’t make it known—and I think that’s part of the problem. When young folks stop speaking about it, or young folks stop noticing that it’s abusive, that’s not okay. I think that’s a big problem. I feel like the way that I got out of it is by physically getting out of those spaces where adultism was common and finding more nurturing and inviting spaces— spaces where I felt like I was allowed to speak.

DIAMOND: Where does adultism show up and what are some of the signs that it is happening?

MARIO: It can show up in so many different spaces, whether it’s in your home, your job, an interview, or an academic setting. And I think one of the common scenes can be two people who are going after the same opportunity, one is younger and one is older, and the adult may get the opportunity because of the perception of the experience or wisdom that they might have. That’s a sign of adultism that I’ve definitely experienced personally.

QUINN: There can be physical signs of adultism. So, if there is a team of young people and adults, and all of the adults in the room are directing their questions at the other adults, and all of the attention is on the adults, the young people feel that. Or even how attentive people seem to be when an adult is talking versus when a young person is talking. Also, I feel like it shows up—and I’m thinking personally about family—when big decisions are happening within a family and nobody is asking for your opinion and your voice is not heard. It comes down to adults taking ownership over the decision-making. And that process can come off as quite toxic—with lots of clashing and argument. It might look like that sometimes, but other times, depending on who you are as a person, it may just come out as silence. Sitting in silence. You just have to listen to what they say and obey whatever is being said.

PAULA: I agree with everything that is being said and I’ll also say that a space that it shows up for me is within my own friend group. I might want to do something, or speak up about something, or just move forward with an idea, and some of my friends might be saying, no, you’re too young for that. You shouldn’t be thinking about that. They won’t listen to you. That can be really toxic, in the sense that I want to move forward with this dream and this idea, but my own peers can be bringing my confidence down and not supporting me on that. Some of the signs can be the wording, right, like: You’re too young. You should go ask an adult first. You should have asked permission first.

SAMANTHA: Hearing Paula speaking triggered something for me. I think that a lot of this peer-to-peer behavior has to do with the internalized things that have been going on for years—young people have been told all of these things. We’ve been told things like that for years and years by parents, teachers, even mentors who say that they have our best interests in mind.

DIAMOND: I’ve also experienced this in situations where I am working with adults. I’m working with people who claim that I am there working just the same as them, doing the same job as them, but because I am younger than them, they feel as if they have to facilitate everything I do, or find some other way to bring me down.I’ve experienced that a lot with adults who ask me to work with them, but then they feel like they have to adult-splain to me, like they have to spell everything out for me. And it makes me think: what do you have me here for?

SAMANTHA: This can all become really toxic when it starts to move away from a with relationship and toward somebody speaking to you or for you. Which is when we can start talking about tokenization. When you start being used as a token and people can say, I taught this person and it’s because of me that they are great. And I’m thinking, no, I’m great because I’m Sam. I’m great like that because I’m me. That’s when it starts becoming toxic because, for the youth, once they get out of that space, they might start thinking: Am I not worth it because I am not with them anymore? What if I’m not as good anymore?

BRIANNA: It seems like sometimes when a young person leaves an organization, group, or business, the adults are expecting us to be at a loss, like we won’t have direction. For me personally, I don’t feel like I’m at a loss, I often feel like I’m regaining my own voice—I’m regaining my own ideas, values, and beliefs. Like Diamond said, I don’t need anybody to explain every little thing to me. In my mind, when you hire somebody, you should know that they are qualified and say: Here is your position, go run with it. I already know that you are going to do what you say you’re going to do, and you are going to be excellent.

QUINN: I’m thinking about this from the fundraising perspective because I’m on the fundraising team at Rising Youth Theatre (in Phoenix, AZ). Among any nonprofit that works with young people, but I think particularly with arts organizations, there is some really gross fundraising that is really manipulative and, like Sam was saying, really tokenizing. That can be another form of adultism in terms of how youth are involved in the marketing and fundraising; [How they are] used as a tool, really, of capitalism.

DIAMOND: I experienced this so much when it comes down to working with adults. Especially with what you all have been saying about adults suggesting that my accomplishments are what they are because of them. No, it’s because of me. It’s because of what I did. But they don’t really want to give you that credit. They want to make sure that you know that it’s all bottled up right here with them. I have definitely experienced that. Also, as you all mentioned, with fundraising: I do a lot of different fundraising for some of the organizations that I’m with. They’ll put me in the fundraiser because I’ve been a young person in their program. They’ll use me for this and that, but they don’t really take a moment to look at you and consider hiring you because, “Oh, she can do this for free because she’s young. She doesn’t really need work. We want to let everybody know that we are doing so much for her—she’s all this and all that”—but am I getting paid like an adult?

DIAMOND: How does adultism show up in intergenerational spaces?

BRIANNA: This picks up on what we were discussing before, but I think it shows up in how work is put on me, and how I’m treated. The organization might say: You are capable of doing this, but you’re just going to be a volunteer. I’m not being paid for any of my work—for any of the skill sets that I am bringing to the table. I’m doing this for the mere fact that I believe in the mission. I feel like I’m a bit silent on how to advocate for myself, how to move forward.

PAULA: For me, there’s something about putting someone on a pedestal. Often it can be a young person putting an adult on a pedestal. I can only speak from my own experience, but I have put adults on pedestals because I’m thinking to myself: They’re dope, they’re always right, and I don’t care if my peer is disagreeing with what they have to say. This can be toxic, right? I have friends who have come up to me and said, you know, you’re putting this person on a pedestal. They shared an idea that was in conflict with some of our values, but you agreed on it, and you completely shut down what I was trying to share. And I thought, dang, I didn’t realize I was doing that. By being called in by my friend, I was able to understand the ways that adultism can show up in my body. So, I’m trying to learn how to not put people on a pedestal and just see them as people—because we’re all equal. Ultimately, I’m thinking: What does it look like to have a healthy, loving, joyful intergenerational space where young people and adults are together making decisions not just as adults and as young people but as a whole?

QUINN: One of the ways that this also shows up is in theater spaces, and I’m especially thinking of traditional theater, whether that’s in a high school or in a theater company: There are very clear youth and adult hierarchies there. The adults are the directors, the designers, the choreographers and the young people—they’re building sets and making costumes, but they’re not actually designing anything. Oftentimes the adults are allowed to hold the vision, they’re allowed to hold the creativity, and the young people are just there to execute.

PAULA: What does a healthy intergenerational relationship look like?

QUINN: It’s a lot of the same things that any kind of relationship needs to be healthy. So, a reciprocation of respect and trust. Also, a willingness to ask for help on both sides. So, as a young person, I need to be prepared to say sometimes, I don’t have a Ph.D., so I don’t know what that means. Can someone explain it to me? And then at the same time, adults need to also be willing to ask their young peers for help, because young people have things to offer too, and we have ways that we can mentor adults.